A Nation of Hoarders Passes the Tipping Point – Pay Attention to the States

This article was originally published on eBooleant.com. Join the over 800 investment professionals who viewed Dr. Fischer's post on this topic in his feed on Linkedin.

Extraordinary monetary policy has become the norm globally. And as it continues, classical models of the economy find obsolescence. The Phillips Curve is a prime example of a maxim which could not survive the Fed’s new normal. This shift to extraordinary monetary policy has had vast implications for interest rates and credit, implications yet to be fully appreciated. The economy and the market have still not adapted to the new American hoarding culture or what it means for policy.

The role of hoarding in the current crisis is apparent. Consumers, even with heavy pandemic aid, have been aggressive hoarders. Paper towels have been the cause celeb, but it is cash hoarding which has severely negatively impacted the economy. Hoarding has moved from a personal trait to a systemic structural weakness.

Almost a crime for individuals

Hoarding has long been a survival mechanism for both public and private entities, saving in times of plenty to prepare for times of shortage. At the private level, pathological hoarding has been classically characterized by the miser. Dante, for example, had a distinct objection to cheap priests whom he cast into hell. More recently, some of the rich and famous have joined the dubious list of Andy Warhol like hoarders.

Hoarding becomes a public sector problem with mass behavior. While interesting, individuals play little economic role compared to the millions of economically motivated hoarders in a panic. These reached special prominence in the Great Depression. In fact, hording of gold was an important factor that led Franklin Roosevelt to abandon the gold standard in 1933. He effectively made possession of gold hoards a crime in Executive Order 6102.

Fed policy and public sector hoarding

This pandemic is the third great economic event of the last century. It joins the Great Depression and the Great Recession as unparalleled economic shocks with accompanying mass hoarding. The Great Depression experienced a banking crisis as people rushed to withdraw funds. It seems unintuitive that the withdrawals were part of a great savings glut but the money, in one form or another, went into savings under the pillow. While there is a myriad of differences, the Great Recession, like the Great Depression saw cash hoarding. Individuals, and corporations collapsed the velocity of money during the Great Recession.

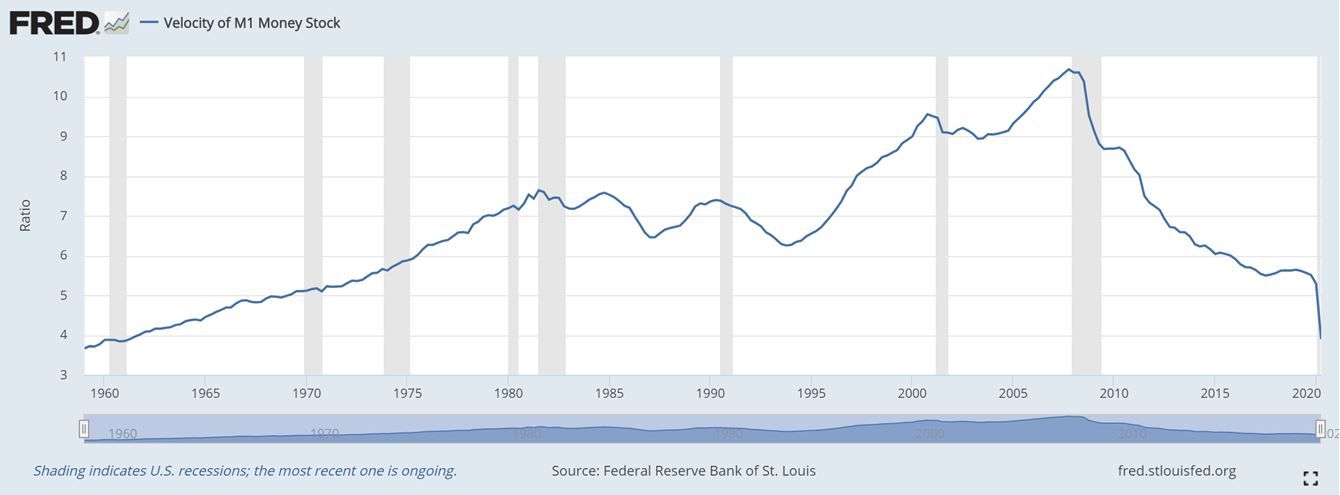

There are a variety of ways to measure the amount of money in circulation. One of the narrowest is the Federal Reserve’s M1, which is essentially cash. The velocity of money is the nominal GDP divided by the stock of money. The velocity of M1 fell precipitously in 2008 and 2009 as Chart 1 shows. The nation turned into a country of hoarders at the individual and corporate level and hasn’t looked back.

In fact, there is good evidence that the nation was tending toward hoarding much earlier than that. If we look at a more encompassing measure of money from the Fed, MZM, that becomes clear.

An understanding of MZM will clarify why this is important.

“MZM (money with zero maturity) is the broadest component and consists of the supply of financial assets redeemable at par on demand: notes and coins in circulation, traveler’s checks (non-bank issuers), demand deposits, other checkable deposits, savings deposits, and all money market funds. The velocity of MZM helps determine how often financial assets are switching hands within the economy.”[1]

Essentially this is the money which supports buys and sells in the economy, dollar for dollar. If there aren’t enough dollars for the trades, it constrains the amount of trades and is a drag on economic growth. So, Chart 2 shows that cash savings/hoarding started back in the 1980s. In the early years it was hard to say it was hoarding and not just necessary savings. Now, however it is quite clear.

Chart 2 contains a critical clue about where we are too. The velocity is now less than one. Money in the economy is not turning over fast enough to support the current size of the economy.

Chart 2 Velocity of money, MZM

The states and cities will hoard too

Nor are the states and cities immune from the need for cash savings. The Great Recession was the great teacher for the states. The Great Recession forced a substantial contraction in state programs as revenues collapsed. Nowhere was this more apparent than in California and it was California that led the way to a record level of rainy-day funds before the pandemic.

With or without another federal pandemic package, the states should see that their saving rate was far too low and that rainy-day funds need to be multiples of prior levels to maintain continuity in public services during the next crisis. And issuing state bonds in a recession has very limited utility. The states need an immediate replacement for a decline in tax revenue. They need cash.

Even with the private sector hoarding, the states can accumulate the cash. State level hoarding will crowd out the private sector because state taxing power gives it first claim on any dollar in commerce. The states need Congressional assurance that building their savings beyond a minimum level is not necessary because federal aid programs will supply cash to the states in a crisis. Hoarding is not necessary to maintain current programs.

It may be hard to imagine the states as hoarders now. But it should be expected given the move culturally to a hoarding society and the current frequency of fiscal crises. Indeed, it’s hardly just a US problem. Fiscal hoarding is an international problem for which Japan is often cited as the failed model. But the problem is now falling to the UK which is considering negative interest rates to cope.[2] Failure to see states and cities as potential hoarders will only exacerbate our monetary problems.

[1] Velocity of MZM Money Stock

[2] Letter from Sam Woods ‘Information request: Operational readiness for a zero or negative Bank Rate’

We hope you enjoyed this article. Please give us your feedback.